Introduction#

For thousands of years, agriculture relied on direct observation and manual record-keeping. As humans transitioned from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to organized farming, farmers and agricultural societies developed methods to identify and categorize different crop types based on visual characteristics, growth patterns, and local knowledge. These traditional approaches laid the foundation for understanding crops but were limited in scale and accuracy. Today, by leveraging cutting-edge tools such as decentralized storage of remote sensing data and advanced machine learning models, we can unlock unprecedented insights into crop patterns while making this valuable information accessible to farming communities worldwide.

The Rise of Remote Sensing#

The advent of aerial photography in the early 20th century marked a turning point in agriculture, introducing the concept of remote sensing. For the first time, farmers and researchers could gain a broader perspective on crop distributions and patterns from above.

This revolution accelerated with the launch of Earth observation satellites in the 1970s. These satellites transformed crop classification through innovations such as:

Low-Resolution Imagery: Early satellite sensors enabled broad-scale mapping of agricultural regions.

Multispectral Sensors: These sensors allowed for detailed analysis of crop health and vigor by capturing data across multiple wavelengths.

Vegetation Indices: Tools like the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) improved distinguishing between crop types based on spectral signatures.

These advancements laid the groundwork for modern crop classification systems, which now integrate high-resolution satellite imagery, foundation models supporting machine learning tasks for classification, and cloud computing to provide accurate and timely agricultural insights.

The Role of Decentralized Systems#

As crop classification techniques continue to evolve, there is a growing focus on making these technologies accessible to smallholder farmers and developing countries—key players in global food security. Decentralized systems like Filecoin offer innovative solutions to address challenges related to data accessibility and storage:

Data Storage and Access: Filecoin provides a decentralized storage network that enables secure storage and retrieval of datasets. This is particularly valuable in regions where traditional cloud services may be unreliable or inaccessible.

Trustless Environment: With cryptographic proofs and economic mechanisms at its core, Filecoin creates a trustless environment for data sharing. This fosters collaboration among farmers, researchers, and policymakers without reliance on centralized authorities.

Smart Contracts: Processes such as crop insurance can be automated by leveraging smart contracts on decentralized networks. This ensures timely compensation for farmers affected by adverse conditions like droughts or pests.

By combining advanced remote sensing technologies with decentralized systems, we can create a more equitable and resilient agricultural ecosystem—one that empowers farmers with the tools they need while preserving critical agricultural data for future generations.

From Theory to Practice: A Multi-Temporal Crop Classification Pipeline#

While understanding the history and potential of crop classification is crucial, the real power lies in practical application. Partnership between NASA and IBM Research released their open-source Geospatial AI Foundation Model (FM) last summer, trained on Harmonized Landsat Sentinel-2 satellite data (HLS). Researchers in collaboration with Clark University’s Center for Geospatial Analytics worked on adapting the model for applications such as time-series segmentation and similarity research.

In this blog post, we’ll use Prithvi-EO-1.0, a temporal vision transformer, and Clark CGA’s implementation for multi-label image classification to classify crop types. In the decentralized spirit of the Easier Data initiative, we’ve customized Clark CGA’s implementation by retrieving the content from IPFS with the ipfs-stac python library.

Data Generation Pipeline#

This first step is crucial. Fine-tuning any model relies on quality training data. Crop-type labels are curated from the USDA Cropland Data Layer (CDL) and scenes from NASA’s Harmonized Landsat and Sentinel-2 (HLS) to capture snapshots of time across the growing season. In addition, a reproducible process is necessary to transform and prepare data to be sent through our model. A breakdown of this process is provided below, but don’t sweat if you’re not familiar with these GIS and imagery processing tasks, we’ll also check out a practical example later on. The steps are as follows

Prepare CDL chips and identify intersecting HLS scenes that correspond to each chip. > We’ll get into more detail about “chips” below, but are basically our unit of analysis.

Determine candidate scenes that meet cloud cover and spatial coverage criteria.

Download the selected scenes’ spectral bands (Blue, Green, Red, Narrow NIR, SWIR1, SWIR2) from IPFS.

Reproject each scene based on the CDL projection

Merge scene bands into a single image and clip to chip boundaries

Discard clipped results that do not meet QA and NA criteria

Model Training and Inference Pipeline#

The model pipeline offers several pathways depending on your specific needs.

Training a New Model#

The Prithvi foundation model leverages temporal data to capture crop development throughout the growing season. The model analyzes three distinct timeframes of the same location, where each timeframe reveals different stages of crop growth and field conditions. The training process combines these temporal snapshots with labeled data from the CDL to teach the model to recognize crop-specific patterns as they evolve over time.

Testing and Validation#

After training, we evaluate the model’s performance using separate test datasets containing labeled chips that the model hasn’t seen before. This validation process helps us understand how well the model can distinguish between different crop types and land cover classes across various agricultural regions.

Model Customization and Inference#

After assessing the model’s performance, we can customize it for specific applications or unique agricultural regions. This process, known as transfer learning, is an iterative process by fine-tuning the model on new data to adapt it to different contexts such as optimizing for particular growing season or climate conditions.

A Practical Use Case: Classifying Corn Crops in the Midwest#

To demonstrate the pipeline’s real-world applicability, let’s consider a specific use case: identifying and classifying corn crops in the Midwest United States. The Midwest, often called America’s Corn Belt, is an ideal study area due to its agricultural significance and the prevalence of corn as a major crop.

Data Sampling: Cultivating Our Digital Crop Patches#

We’ll first set the stage for our analysis by selecting an area of interest (AOI) that represents the Corn Belt. By selecting this AOI, we can focus our analysis on a specific geographic area and gather relevant data for our model training. In addition, the model requires consistent, well-structured data inputs. In this case, we’ll be selecting from a grid of pre-divided square polygons. These polygons serve as our training chips, carefully positioned to capture representative samples of the agricultural landscape.

So far, we’ve identified an AOI and selected some polygons, but what do they represent? Ah, I’m glad you asked! Those square polygon features represent our training “chips,” allowing for a more efficient way of handling large datasets into smaller, manageable data portions. Doing so helps normalize the data, ensuring a uniform size so as to more effectively compare and analyze data across different datasets. These chips will be used for our particular application to clip out portions of the CDL raster layer, giving us labeled data where the pixel value represents a crop type. As for the HLS scenes, the chips will be used to clip our portions of the image for training, which the model was built on, to classify the crop types from the imagery.

Democratizing Data Access: The Power of Decentralization#

Let’s engage in a thought experiment about the future of agricultural data. Imagine a world where decentralized networks like IPFS and Filecoin are widely adopted for storing and retrieving critical agricultural information. How might this reshape the farming landscape, particularly for small-scale and rural farmers? This scenario offers intriguing possibilities that align with broader goals of data accessibility and collaborative farming.

Empowering Local Farming Communities#

Imagine a consortium of small-scale farmers in a rural Midwest community. By leveraging decentralized storage and retrieval systems, these farmers can:

Share Local Insights: Upload and share localized crop data, creating a rich, community-driven dataset that complements broader satellite imagery.

Reduce Dependency: Access crucial agricultural data without relying on centralized servers, which may be unreliable or inaccessible in remote areas.

Enhance Collaboration: Easily exchange information on crop health, pest outbreaks, or successful farming practices within their network.

Ensuring Data Resilience and Accessibility#

Decentralized networks offer unique benefits for agricultural data:

Data Persistence: Critical information remains accessible even if individual nodes go offline, ensuring continuity in research and decision-making. Filecoin’s economic incentives further guarantee long-term data storage.

Reduced Costs: By distributing storage across a network, the cost of maintaining large datasets can be significantly reduced, incentivizing smaller organizations to participate.

Global Accessibility: Researchers and farmers worldwide can access and contribute to the same datasets, fostering global collaboration in addressing food security challenges.

A Practical Example: Real-time Crop Health Monitoring#

Consider how this decentralized approach could transform crop health monitoring:

Farmers use drones or smartphone apps to capture images of their fields.

These images are uploaded to decentralized storage networks, creating a distributed, real-time dataset of crop conditions.

Accessing data from these networks, our multi-temporal crop classification model, provides up-to-date insights on crop health and potential issues.

Farmers can quickly identify and respond to problems like pest infestations or nutrient deficiencies, potentially saving entire harvests.

Leveraging decentralized networks for data storage and retrieval, we’re reducing reliance on centralized data sources and creating a more equitable information landscape. Enabling farmers, regardless of their size or resources, to access and contribute to a shared pool of agricultural knowledge. Where information flows freely, and decision-making is more inclusive with direct collaboration among farmers, researchers, and other stakeholders. As we proceed, consider how this decentralized data approach could enhance agricultural practices in your community or research area.

From Data to Insights#

Now that we’ve explored how decentralized networks can democratize access to agricultural data, and prepared our training chips, let’s dive into the heart of our project: the multi-temporal crop classification model. This model is designed to analyze the prepared data and provide valuable insights about crop types and health across the growing season.

The model examines three distinct timeframes (T1, T2, T3) of the same location, capturing how crop characteristics evolve throughout the growing season. Using extensive agricultural ground reference data to produce a crop-specific land cover data layer, the CDL layer is our reference to understand how well the model is able to characterize the crop types. Each timeframe contains spectral data from various bands, including visible light and infrared wavelengths, which help distinguish different types of vegetation and land cover.

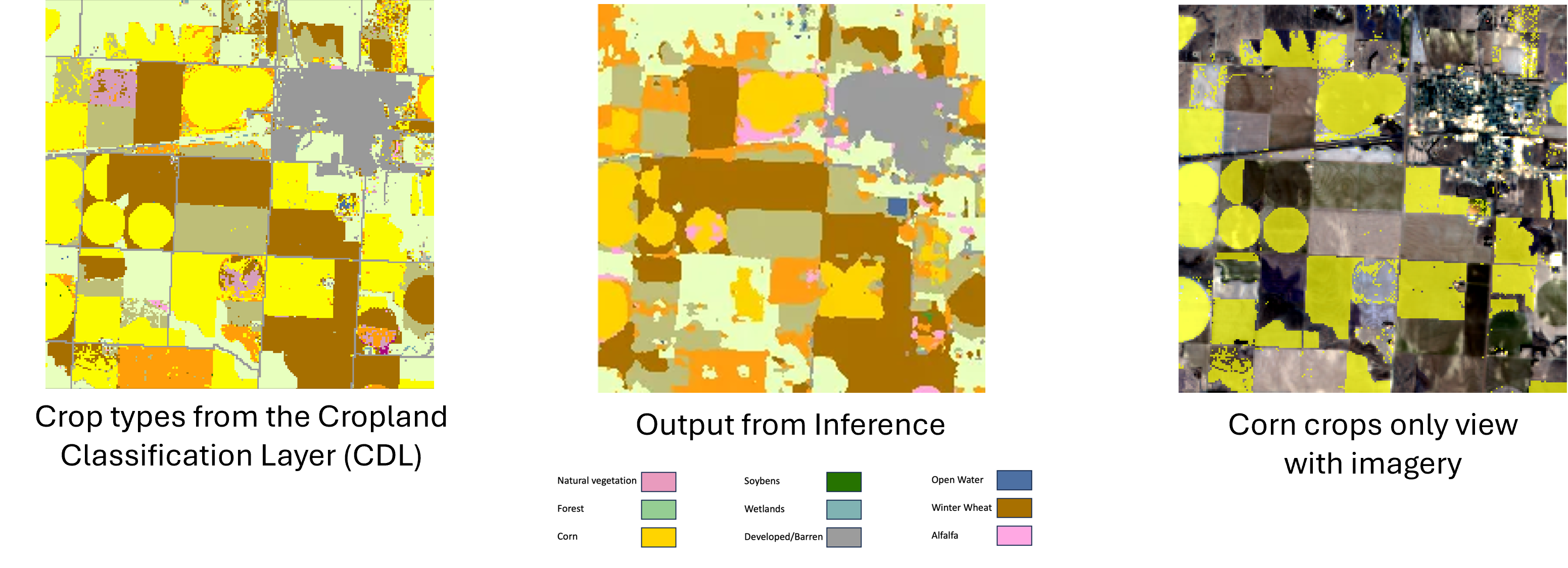

Let’s walk through the process shown in the images:

The top row shows our input data: three temporal snapshots (T1, T2, T3) of the same agricultural area at different points in the growing season.

These three timeframes are merged into a single composite image (Timeframes Merged).

The bottom row shows all the CDL crop types in this area. The model processes the merged imagery with it’s predictions, where different colors represent different crop types that were inferred.

For visual context as to compare the model’s predictions with the actual corn crop, I filtered the CDL layer to only view corn crops on top of the merged imagery.

The final output provides a comprehensive view of crop distribution, as shown in the labeled cropland classification layer, which can be further refined to focus on specific crops of interest, such as corn in our Midwest use case.

Looking Forward#

The future of crop classification in conjunction with decentralized systems is promising. As satellite technology improves in resolution and frequency, combined with advancements in machine learning algorithms, the potential for real-time monitoring and analysis will expand. Moreover, initiatives like those from the Filecoin Foundation aim to preserve humanity’s most important information and NASA’s commitment to open science is crucial in making this content accessible to smallholder farmers and developing countries.

These collaborative approaches address immediate agricultural challenges and contribute to the long-term goals of food security by ensuring that essential information is accessible to all stakeholders involved in agriculture. By bridging the gap between cutting-edge technology and practical applications in farming, we can create a more resilient food system that supports both local communities and global needs