Introduction#

When dealing with large geospatial datasets, such as Landsat 9 imagery, effective management, storage, and seamless transfer of massive data are key challenges for both data stewards and users seeking to access the content. One common solution for bundling and compressing these datasets is using .tar files (a type of File archiver), which aids data stewards in organizing into collections and simplifying data transfer for users. Transitioning into the realm of decentralized systems, Content Addressable Archives (CAR) present a solution akin to .tar files. CAR files, like their traditional counterparts, play a role in maintaining data organization and accessibility in decentralized setups. In this blog post, we’ll look into the technical details of CAR files and explore some practical advantages inherent to InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) and Web3.

What is content in IPFS?#

When content is imported into IPFS, a unique CID (content identifier) hash is generated representing the content itself in the form of a graph tree. This representation can be further decomposed into smaller chunks known as blocks, where each block generates a unique CID hash node linked to the parent hash node. This hierarchical list of linked CIDs is known as a Merkle DAG (Directed Acyclic Graphs).

The Merkle DAG structure is a key part of the InterPlanetary Linked Data (IPLD) protocol, which allows for the use of content-addressable data structures and provides a way to link between different content-addressed data structures.

In IPFS, when we want to identify a specific data object, i.e., file or directory, we’re specifying the hash value from a Merkle DAG root node, known as the content identifier or “CID.” Referring to content by its CID is known as content addressing. Since the CID is unique, we can use it as a link, replacing location-based identifiers (like URLs) with ones based on the content of the data itself. This is a fundamental aspect of the IPLD protocol.

Learn more about the benefits of content addressing within the InterPlanetary Ecosystem.

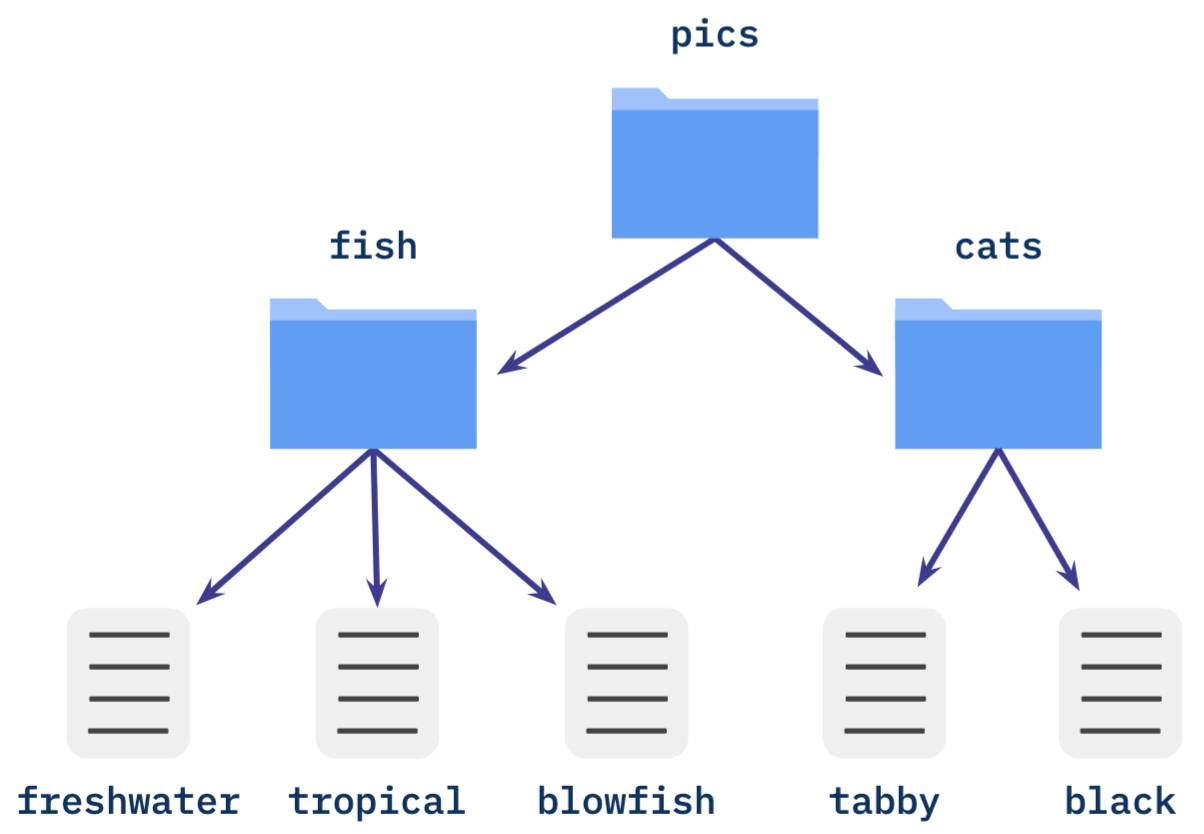

Let’s look at an example based on this directory of files:

Importing the directory of files into IPFS creates Merkle DAGs of the content as shown below. In this example we’ve simplified the DAG representation of the content using two attributes: 1) the name of the file and 2) the data corresponding to the file’s contents. These attributes, when bundled together, make up the data of our node, represented below in the orange box:

The root directory pics is the root node of the DAG with the CID baf8. If we wanted to see all the content in the sub-directory, cats, we would reference the CID baf7 which would return:

When looking at this example, you may have also noticed that the root CID label for the pics directory has a higher integer value compared to the children CIDs for each of the files at the bottom of the graph tree. The reason for this is because representation of DAGs are derived from the bottom up and each node’s CID depends on its descendants. Any alterations to the images or additions/deletions of content from a folder would change the CID value of the parent node. This is because parent nodes cannot be created until CIDs of their children can be determined.

NOTE: The CID labels are purely for explanation. For an in-depth look at the formatting of a CID, see this interactive tutorial on the Anatomy of a CID.

So how does this relate to maintaining and organizing large datasets? Because at the heart of any dataset is its data structure! From Wikipedia, a data structure is defined as:

In computer science, a data structure is a data organization, management and storage format that enables efficient access and modification. More precisely, a data structure is a collection of data values, the relationships among them, and the functions or operations that can be applied to the data.

The choices we make when structuring how our data is organized has significant implications for the types of interactions that can be performed. Therefore, the larger a dataset is, the more important it is to tailor the structure the way we intend to use or access it. Structure gives data meaning and organization, and, in the case of generating DAGs, a unique identifier.

Organizing content#

When we structure individual data elements, we must also consider how we assemble these elements together. In this use case, we organizing the original dataset into collections of Merkle DAGs. Collections of this type have several advantages for dissemination and sharing purposes:

Efficiency: Downloading a single file is often faster than downloading many smaller files due to reduced overhead. This is because each file download requires a separate request, adding significant overhead when dealing with many files.

Reliability: If the download process is interrupted, it’s easier to resume or restart a single file download than multiple individual file downloads.

Ease of Management: A single file is easier to manage, transfer, and keep track of than many individual files.

Preservation of Structure: Archive files can preserve the directory structure and metadata of the original files, which can be important for certain types of data.

Collections of content introduce an extra layer of abstraction in data structuring that impacts downstream usability for dissemination. For example, the Landsat 9 program collects upwards of 750 scenes a day. Each scene contains a set of 21 files which equates to 15,750 files collected daily. Generating this many files daily is one of the many reasons that scenes are organized into collections of .tar files.

In the context of decentralized systems, these advantages apply as well. Just like .tar files, CAR files are used to organize CIDs into collections.

But wait… don’t forget that we’re in the web3 realm!#

The key differentiator here is content-based addressing which enables the capability of partial extractions, the ability to access and extract specific content by its CID within a CAR file. Traditional archive formats like .tar files treat the entire file as a single stream of data, which means to access a specific piece of data, you need to download the entire file. This can be inefficient, especially for very large datasets where bandwidth is the limiting factor. The CAR format is a serialized representation of data, where each piece of data in the collection is individually accessible without the need to read through the entire file.

Note: This is made possible by the inclusion of an index in the CARv2 format, which provides a way to look up the offset of a specific block within the file.

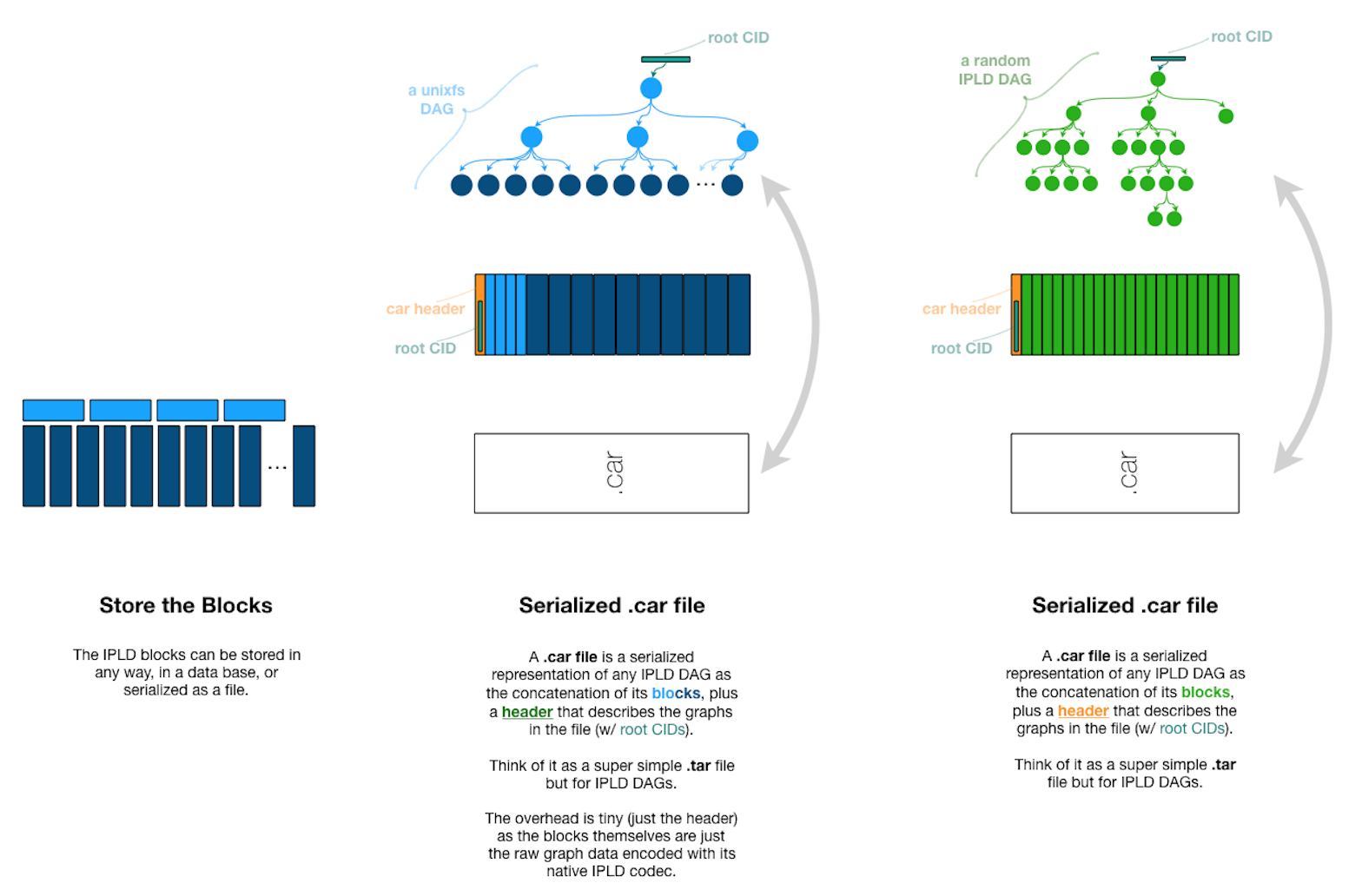

So how do CAR files store DAGs? Let’s take a look.

The diagram above depicts a header block containing details about the DAG followed by the data payload, which is a serialized representation of the DAG. Additional technical specifications and features include:

Header: Begins with a header that includes the version of the CAR format and a list of the root CIDs of the data stored in the file

Data Payload: Contains a sequence of data blocks, each prefixed with the length of the block in bytes followed by the serialized block data

Index: Provides a way to look up the offset of a specific block within the data payload, allowing for random access to blocks (this means you can access a specific block without having to read through the entire file)

Characteristics: Self-describing and self-contained; includes all the blocks and the links between them (so you don’t need to fetch any additional data from the network to access the data in the file)

Pragmatic: Designed to be easy to produce and consume, with a focus on practicality and efficiency; supports both sequential access (like CARv1) and random access (thanks to the index), making it a versatile format for a wide range of use cases

Conclusion#

Organizing and managing large geospatial datasets is challenging as it requires the steward to tailor the data structure in the way users intend to access and engage with the content. Knowing the intricacies of your data is really important, but don’t forget your audience because their expectations for using the data are crucial to developing the underlying data structure.

The shift towards decentralized systems introduces new advantages via content addressing. This approach replaces location-based identifiers, representing files and directories as Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) with a root node known as a CID, or content identifier. The CAR file format enhances this content addressing capability, enabling data stewards to leverage the IPLD ecosystem to structure content in an addressable and linkable manner. This gives users the flexibility to identify and extract the content they need more efficiently.